In the previous section you were introduced to the idea of understanding the notes in a song’s melody using a relative system. However, songs usually have many other notes being played besides the melody. These other notes work together to create rich sounds called chords. In this section we will extend the concept of relative notation to chords and learn how to break up a song into its two basic building blocks: its melody and its chords.

Just as with the notes in the melody, the notes that form the chords of a song typically limit themselves to the same seven notes of whichever major scale the song happens to use. To give a specific example, there are lots of possible chords in music, but if a song is written in C, you are likely to find that it only uses chords that can be formed using the white keys of the piano.

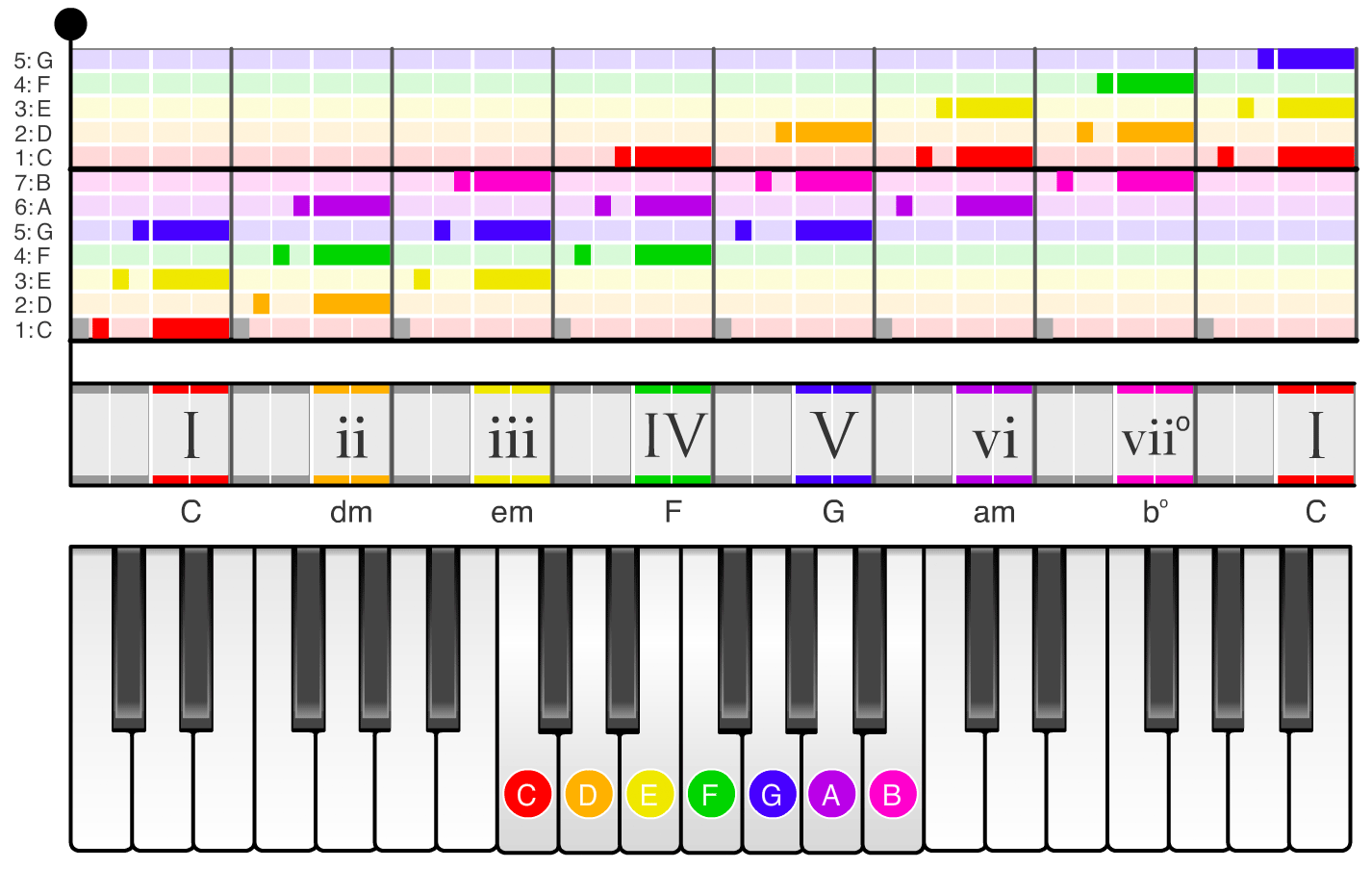

Because there are only seven notes in the major scale, there end up being only seven basic chords that can show up in a given song. Just as we did with melody, labeling these seven possible chords with numbers turns out to be very useful. The first of these chords is built off the first scale degree and for this reason is called the I (“one”) chord.

Since we will now be using numbers to refer to both chords and notes, to avoid confusion, we will use italicized Roman numerals when referring to chords.

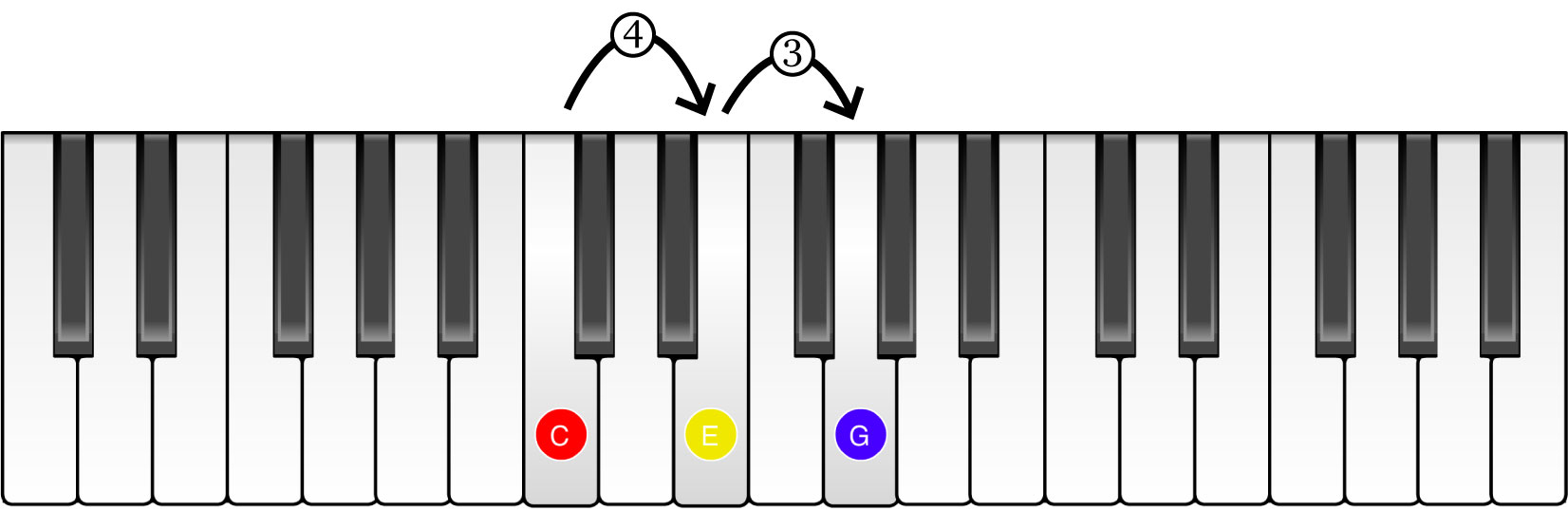

In addition to using scale degree 1, the I chord also contains the scale degrees 3, and 5. In the key of C, this corresponds to the notes C, E, and G and creates a C major chord. Let’s listen to scale degrees 1, 3, and 5 of the C major scale. First we will play each scale degree individually, then we will play scale degrees 1, 3, and 5 (notes C, E, and G) at the same time to create a I chord.

Now you may be thinking that a simple chord like this with only three notes couldn’t possibly be very useful. After all, songs certainly aren’t limited to playing just three notes at once!

It turns out the I chord need not be played with scale degrees 1, 3, and 5 arranged exactly as we just showed you; as long as scale degree 1 is the lowest note, you can reorder the other scale degrees and play any of them more than once. The next example shows a few variations of scale degrees 1, 3, and 5 that also form I chords.

This means that even if it looks like a chord has a lot of notes in it, it’s often likely still just playing three distinct scale degrees corresponding to one of the basic chords.

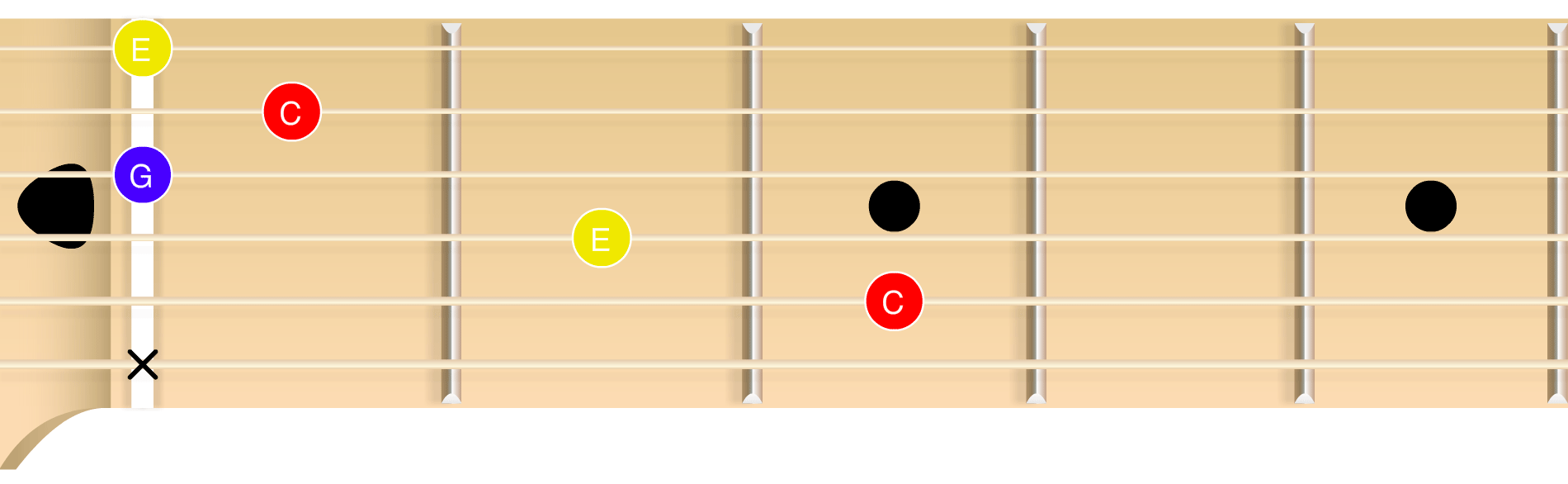

We’ve been showing you a lot of pianos, but this all works the same way regardless of instrument. If you put your fingers on the following frets of a guitar and strum, the strings will play the labeled notes, also resulting in a I chord in the key of C:

Note that even though five strings are played, only three distinct scale degrees are involved: 1, 3, and 5 of the C major scale. Scale degrees 1 and 3 (red, and yellow) are repeated twice. The majority of standard chords on guitar play all six strings yet only involve three distinct notes.

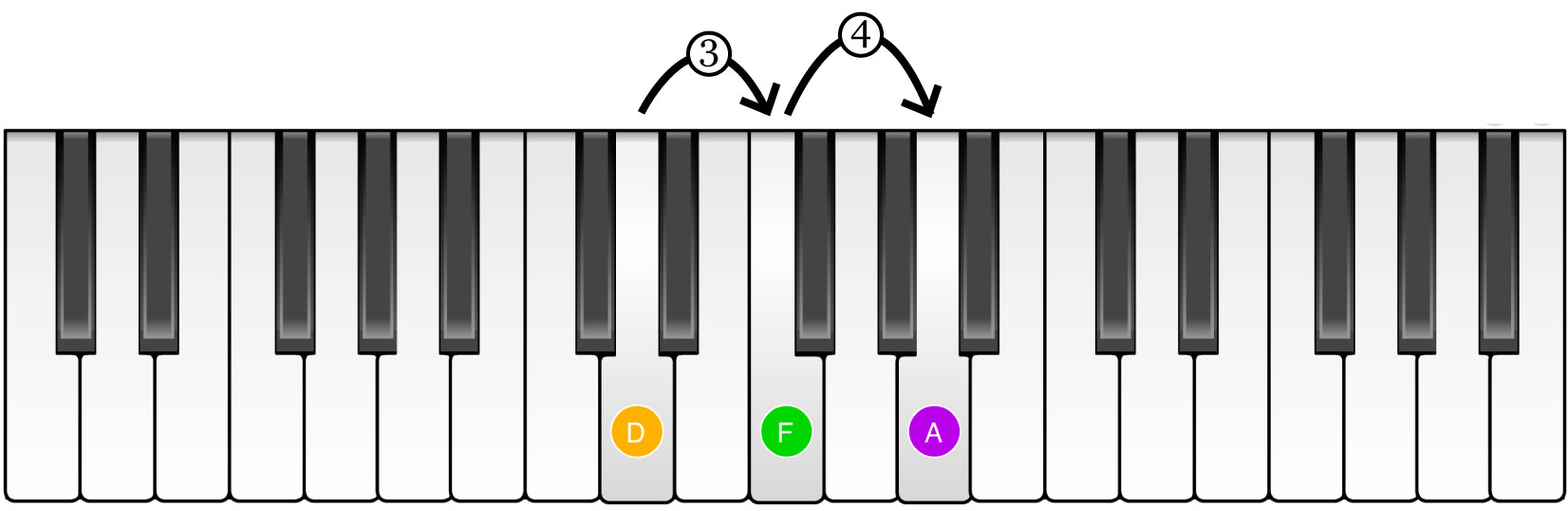

The other six basic chords are built just like the I chord. The ii chord (“two” chord) is built from scale degree 2 of the major scale and contains scale degrees 2, 4, and 6. Let’s listen to scale degrees 2, 4, and 6 of a major scale starting on the note C. First we will play each scale degree individually, then we will play scale degrees 2, 4, and 6 at the same time to create a ii chord.

In the key of C, the ii chord corresponds to a D minor chord. Minor chords have a different sound than major chords (the I chord you heard before is a major chord). The reason for this turns out to be a difference in the relative spacing between the scale degrees that make up the chords. In the next graphic, we illustrate this on the piano by counting the notes between scale degrees 1 and 3 in the key of C (notes C and E), and comparing it to the number of notes between scale degrees 2 and 4 in the key of C (notes D and F). This spacing difference between the scale degrees that make up each chord causes the chords to have a different sound.

When people compare the sounds of major and minor chords, they often say minor chords sound more dissonant and “somber”, while major chords are more “bright” sounding.

To make it immediately obvious whether a chord has a minor quality or a major quality, we use upper case Roman numerals for major chords and lower case Roman numerals for minor chords. This means that we’ll always refer to the second chord as a ii chord (not a II chord) because it is minor.

Since it would be inconvenient to always show the individual scale degrees that make up a chord, we’ll often use a simple “block” representation for chords, as shown below.

The color of the block reminds you of the scale degree that the chord is built on. For example, I chords are built off the first scale degree so they have a red block. In addition, the Roman numeral name of the c hord is inside the box. Notice that the ii chord block, for example, is the same for two different arrangements of scale degrees 2, 4, and 6. That is because any combination of scale degrees 2, 4, and 6 create a ii chord as long as scale degree 2 is the lowest note.

The other five basic chords are built just like the I and ii chords so it’s not necessary to go through each one individually. The next example shows the scale degrees that make up each of the seven basic chords and the Roman numeral “block” notation for each chord.

The IV chord, for example, contains scale degrees 4, 6, and 1; the V chord contains scale degrees 5, 7, and 2. Notice that of the seven possible basic chords, three have a major quality indicated by an upper-case Roman numeral (I, IV, and V), and three have a minor quality indicated by a lower-case Roman numeral (ii, iii, and vi). The last chord, vii°, is neither major nor minor; its quality is called diminished (represented by lower case numeral with a degree sign next to it). The vii° chord, however, is not as common in popular music so it will be treated later.

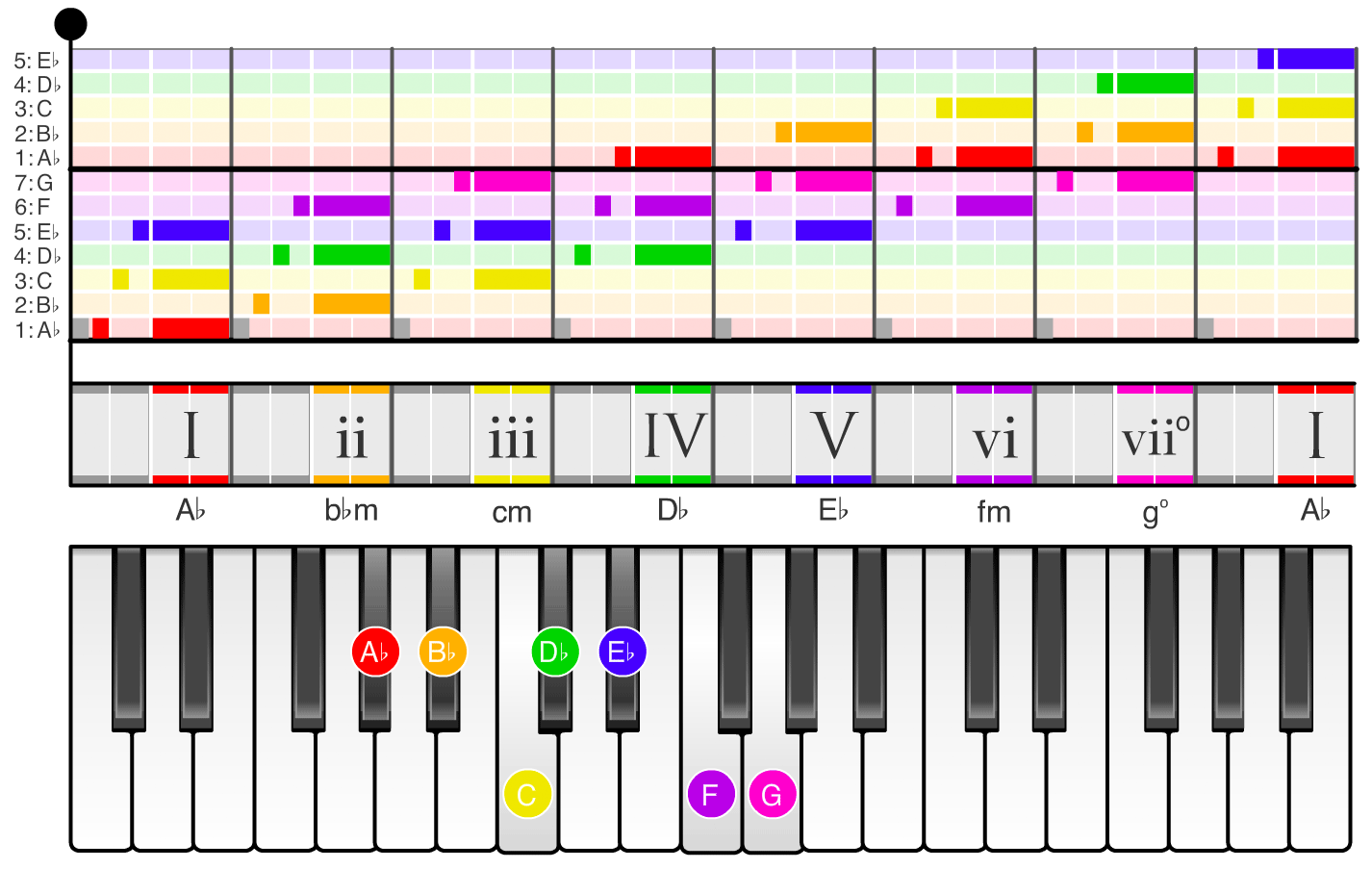

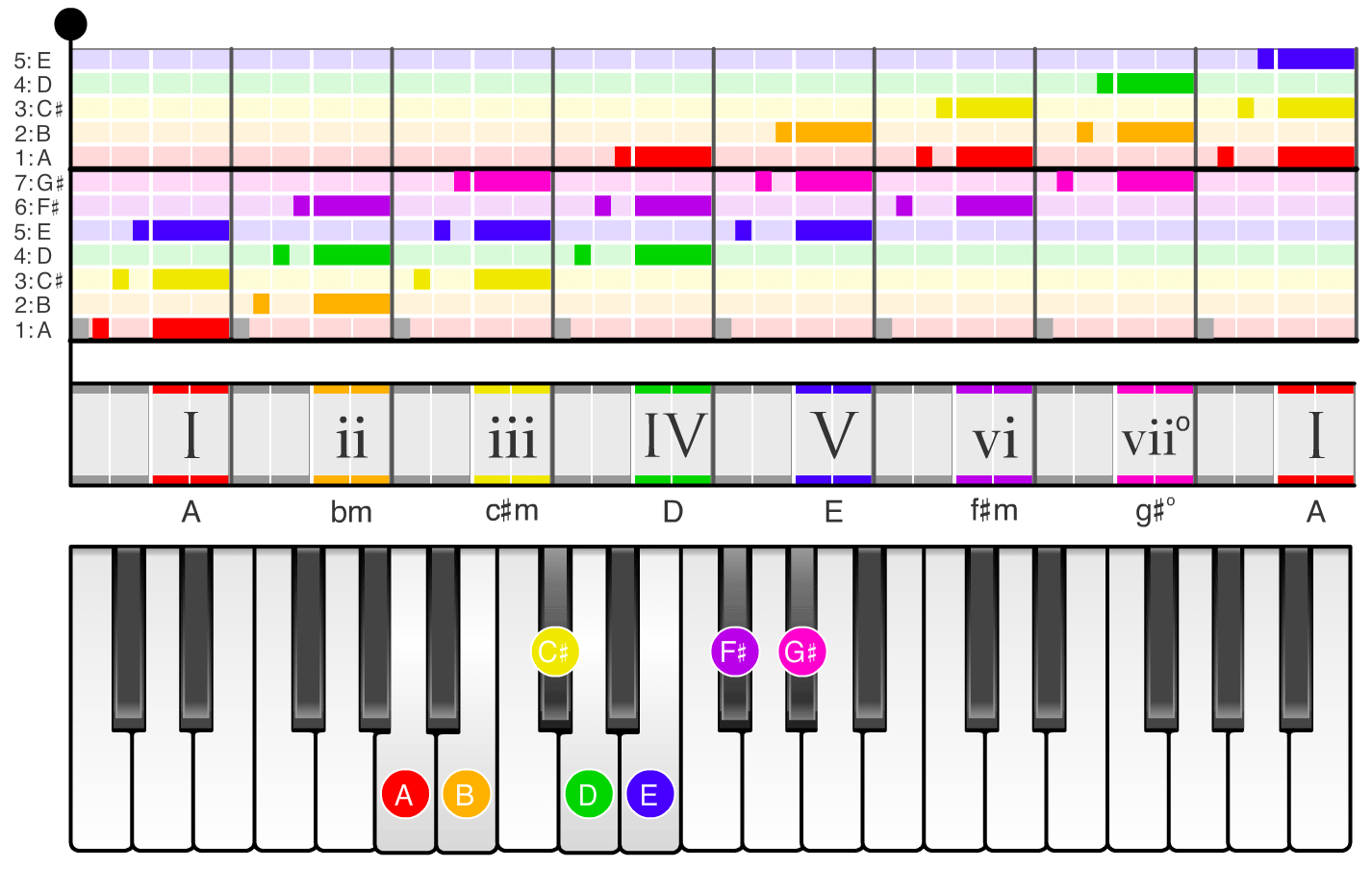

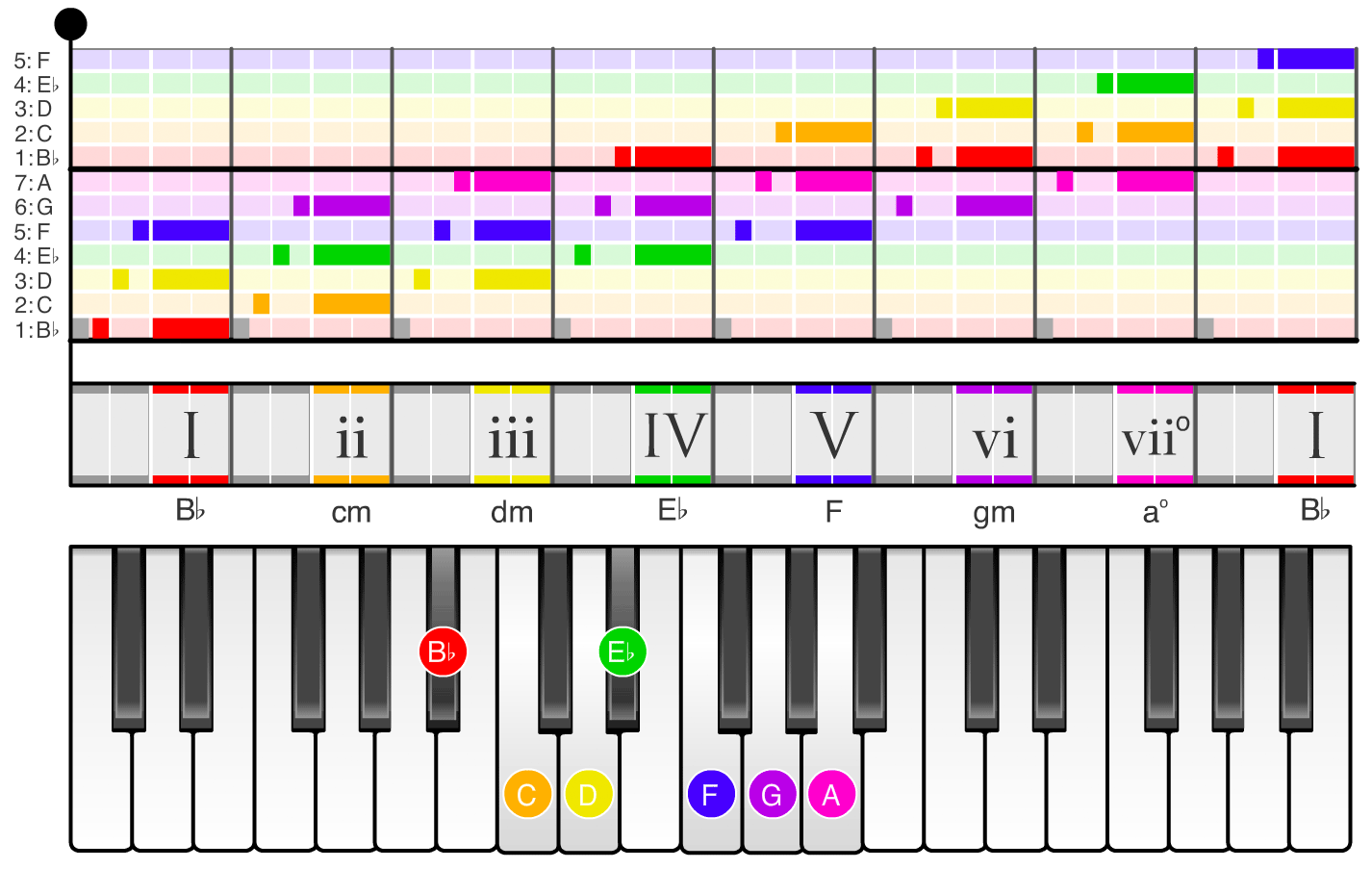

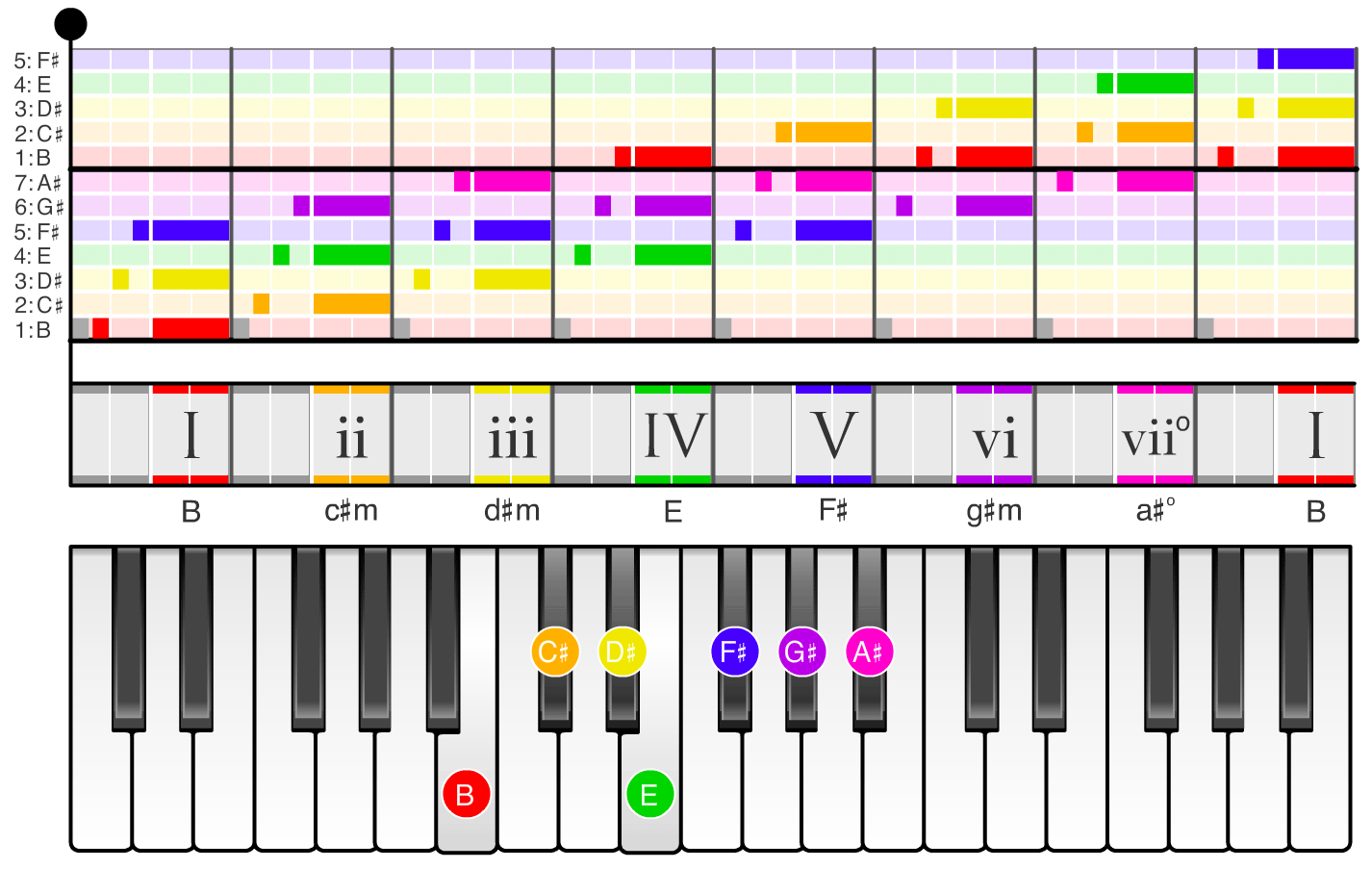

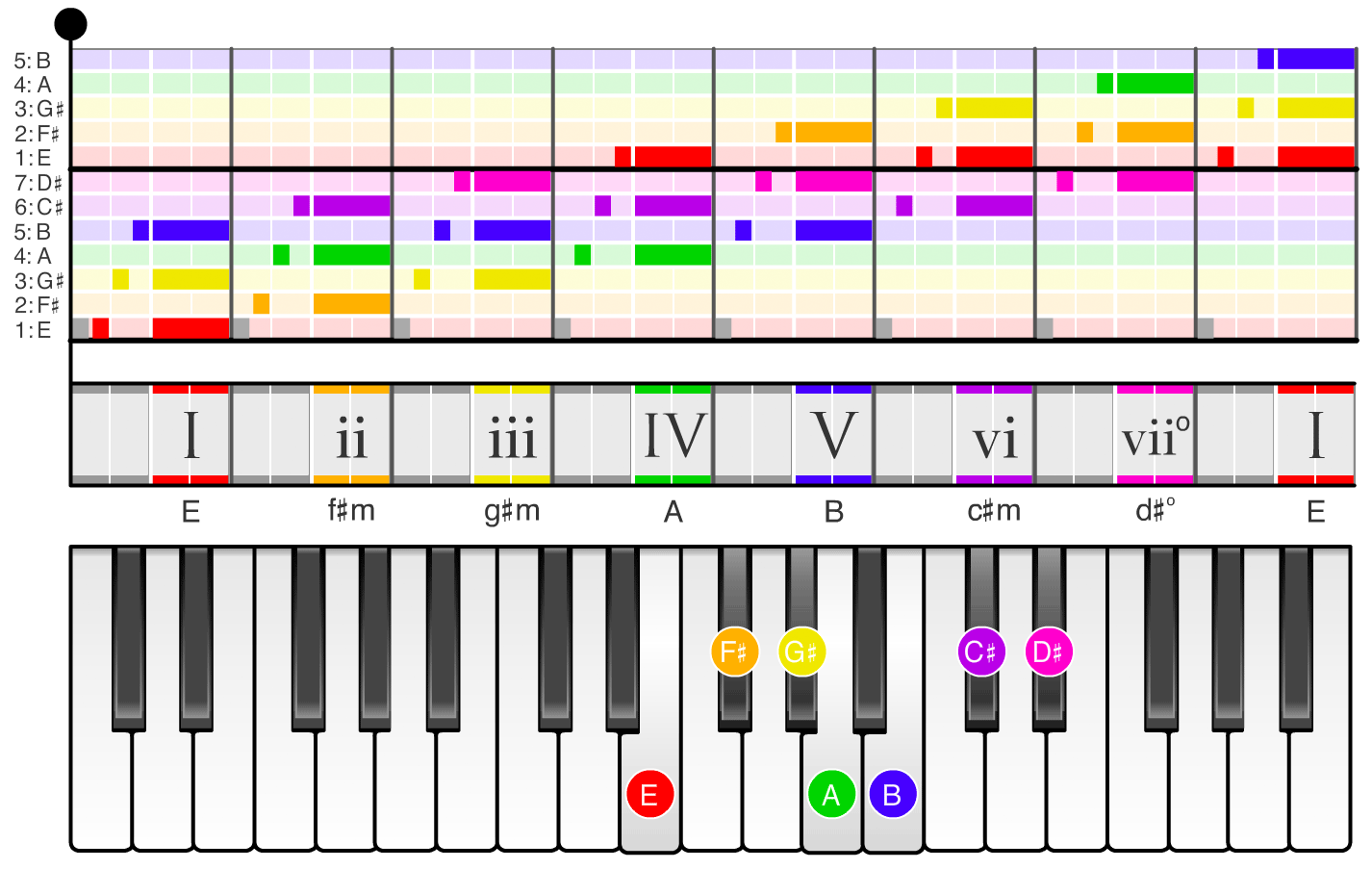

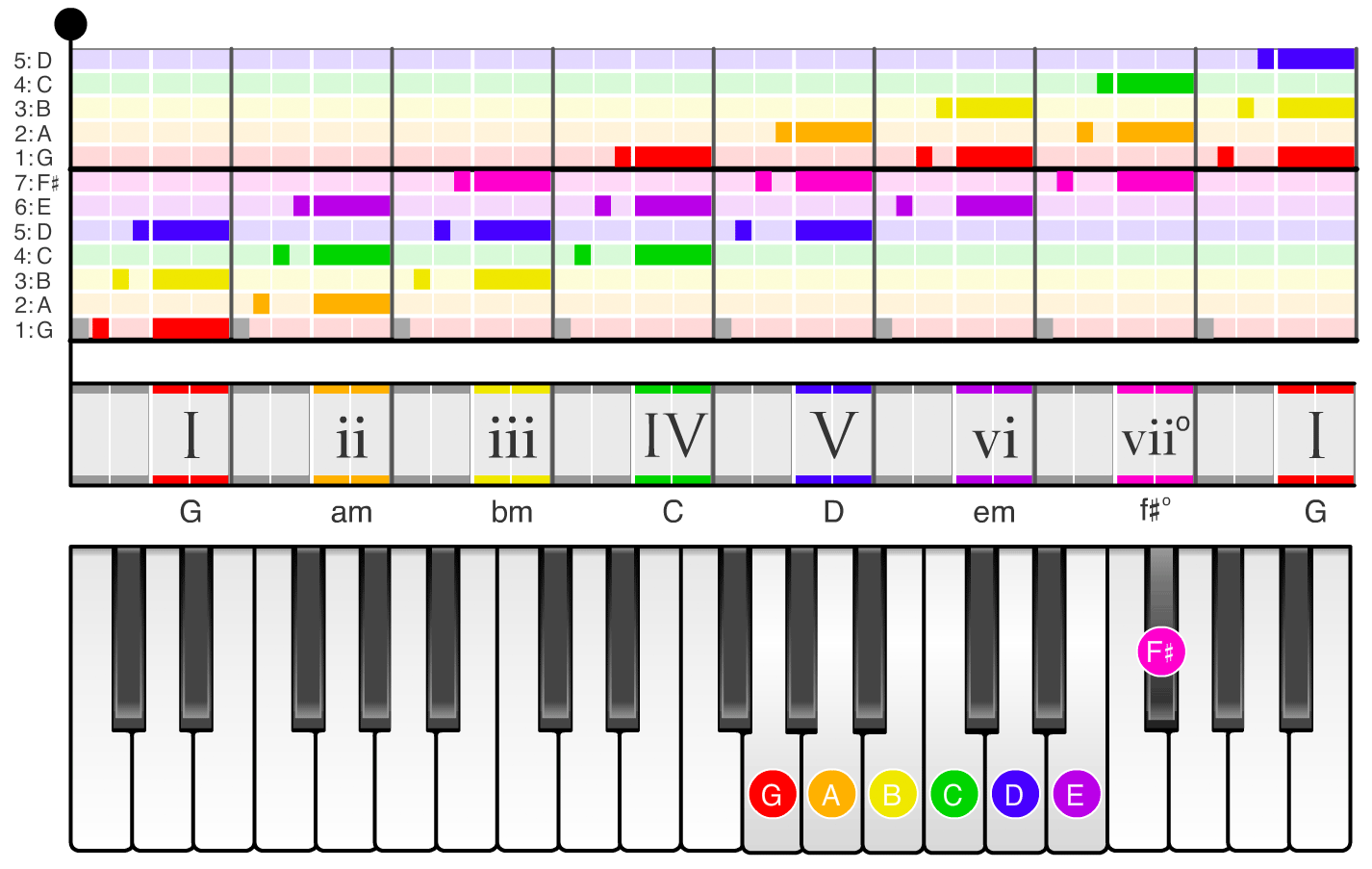

If you swipe through the images in the carousel below, you can see the names of the scale degrees (1, 2, 3, ...) and chords (I, ii, iii, ...) in each of the twelve keys. For example, if you swipe to the the A major scale (the second image in the carousel), the chord names change to A, bm, c#m, D, ... and the notes on the piano shift so the scale starts on the note A. If you swipe to the the D major scale (the sixth image in the carousel), the chord names change to D, em, f#m, G, ... and the notes on the piano shift so the scale starts on the note D.

Next up: Combining Chords And Melody