Review

From the perspective of stable vs. unstable scale degrees, which of the two melodies below would you expect to have more tension?

We just learned that a note’s position in a measure affects how much importance it has. Notes on strong beats are more prominent, notes on weak beats are less prominant. But that is only part of the story. Another factor that influences the melody are the notes contained in the chord being played at that time. Recall that when a chord is played, it is actually a combination of three scale degrees. For example, when a V chord is being played, the other instruments are playing scale degrees 5, 7 and 2.

When a melody contains a note that is also part of the chord being played in the background or accompaniment, there is a sense of stability because the melody is reinforcing the harmony that is being used. Scale degrees in the melody that coincide with the underlying harmony are called stable scale degrees. Knowing the stable scale degrees of each chord is an extremely important tool for melody writing. For the first few examples in this chapter we will highlight the stable scale degrees in the melody staff above each chord.

Unstable scale degrees refer to the scale degrees that are not contained in the underlying harmony. For a V chord, these are 1, 3, 4, and 6. Similarly, when a IV chord is playing, the stable scale degrees are 4, 6, and 1. The unstable scale degrees are 2, 3, 5, and 7.

Review

In which of the following chords is scale degree 5 unstable?

Both stable and unstable scale degrees are important for constructing a good melody. While hanging around stable scale degrees adds security and stability to a melody, spending time on unstable scale degrees adds tension. Tension is a good thing in music, and writing a good melody involves properly balancing these two opposing forces. This balancing act shows up again and again in music, and we’ll come back to it frequently in this book. To demonstrate how the use of stable and unstable scale degrees affects the feel of a melody, consider the following examples.

The melody in the chorus of “If We Hold On Together” (the theme from the motion picture The Land Before Time) is composed mainly of stable scale degrees. Using only stable scale degrees tends to create safe, pleasant, (but at times predictable) melodies. Depending on the context in which the music is meant to be heard (in this case, a happy scene from a children’s movie), this might be exactly what is desired.

Unstable scale degrees on the other hand add dissonance since they are not contained in the accompanying chord. The right amount of dissonance can make wonderful melodies; too much dissonance, however can lead to disaster.

Review

From the perspective of stable vs. unstable scale degrees, which of the two melodies below would you expect to have more tension?

Let’s listen to the two melodies below:

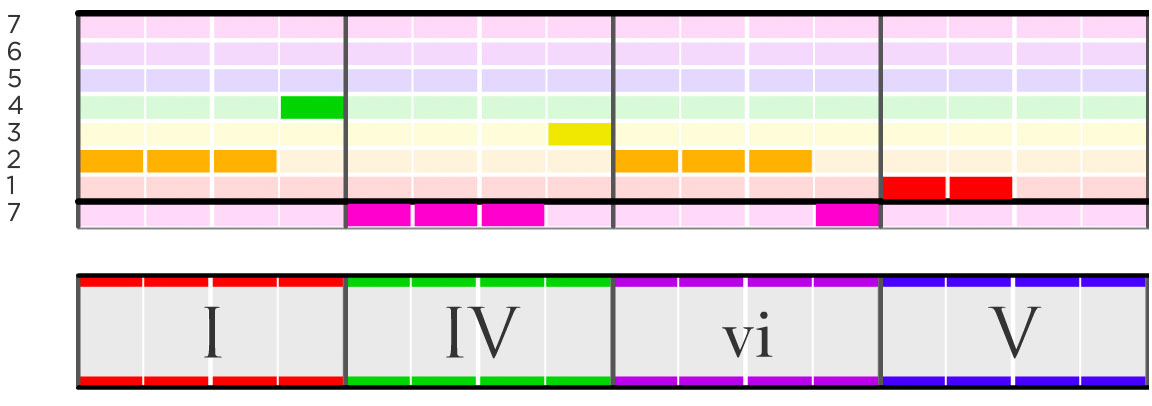

Just because the unstable scale degrees in the second melody sound particularly toxic should not scare you away from using them entirely. The vast majority of melodies contain a combination of stable and unstable scale degrees. The melody from “Home” by Daughtry is one example of a song that balances stable and unstable scale degrees:

The amount of tension that an unstable scale degree contributes to a melody is dependent upon several factors. For instance, the location of an unstable scale degree in a measure (i.e. the beat that it falls on) will greatly enhance or reduce the extent to which it feels unstable.

In general, unstable scale degrees in the melody do not contribute much tension to the song if they are played on weak beats. When unstable notes are used on weak beats to link two stable scale degrees together they are called passing notes. Notice that even the very stable “If We Hold On Together” example contains a passing note in the last measure. Using passing notes is a good way to give some life to your melody without adding the tension that comes with an unstable scale degree on a strong beat. Listen below to Melody A from the previous example, except this time adjacent stable scale degrees are connected using passing notes.

Notice that passing notes, although technically unstable, do not contribute much instability to the melody since they are on weak beats.

To hear how a melody sounds with unstable scale degrees on strong beats, listen to “Sun and Moon”, the famous ballad from the musical Miss Saigon:

Here the melody generates a lot of tension by putting unstable scale degrees on beat 1 of several measures (see measures 1, 2, 5, 6, 7). This tension however never gets out of hand, because in each case, it is resolved by the following note. For example, in measure 1, scale degree 2 is unstable in the I chord, but resolves to the stable scale degree 3. In measure 7, scale degree 7 is unstable in the vi chord, but resolves to the stable scale degree 1.

Generally, when an unstable scale degree appears on a strong beat (beats 1 or 3 in a 4 beat measure, or beats 1 or 4 in a 6 beat measure) at some point the melodic line should resolve to the nearest stable scale degree (above or below). This technique of creating tension and resolution is a standard and effective technique for building interesting melodic lines. The key is not to let the tension build up too much (as in Melody B from before), otherwise your melody may be too unstable to resolve.

Let’s take a look at another example in “Mr. Brightside” by The Killers. At this point, we will remove the stable scale degree highlights on the staff. We challenge you to continue to think on your own about every melody in terms of whether the notes are stable or unstable in the accompanying harmony.

Here the melody also makes use of unstable scale degrees on strong beats. For example, scale degree 4 on the first beat of the I chord and scale degree 2 on the first beat of the vi chord are both unstable notes on strong beats that resolve to their stable neighbors.

Check For Understanding

In the following section of “Breakaway” by Kelly Clarkson, there are two unstable scale degrees that occur on weak beats, and two that occur on strong beats. Identify them.