In this chapter we discuss the use of chord inversions, where a subtle reordering of the notes in a chord can significantly alter its function. Inversions will give you access to a whole new harmonic toolset that allows more flexibility and creativity in your songwriting.

Every chord you’ve learned so far has contained exactly three unique notes (scale degrees). In the introduction chapter we learned that, while there are many ways to arrange these notes to create a chord, under normal circumstances the bottom or root scale degree is always the same (a I chord uses scale degree 1 on the bottom, ii uses scale degree 2, etc.)

Inverted chords do away with this last stipulation and allow the bottom note to be any of notes that make up the chord. When the lowest note or bass note is not the root of the chord, we say that the chord is in an inversion. The basic chords have three notes so there are three possibilities for the bass. When the bass of the chord is just the normal root of the chord (scale degree 1 of a I chord, scale degree 5 of a V chord etc.), we say that the chord is in root position. If instead the next note that makes up the chord is in the bass, the chord is said to be in first inversion. A I chord (which is made up of scale degrees 1, 3, and 5) in first inversion would have scale degree 3 in the bass. When the third note that makes up a chord is in the bass, we say that the chord is in second inversion. In a I chord, this would occur when it is played with scale degree 5 in the bass.

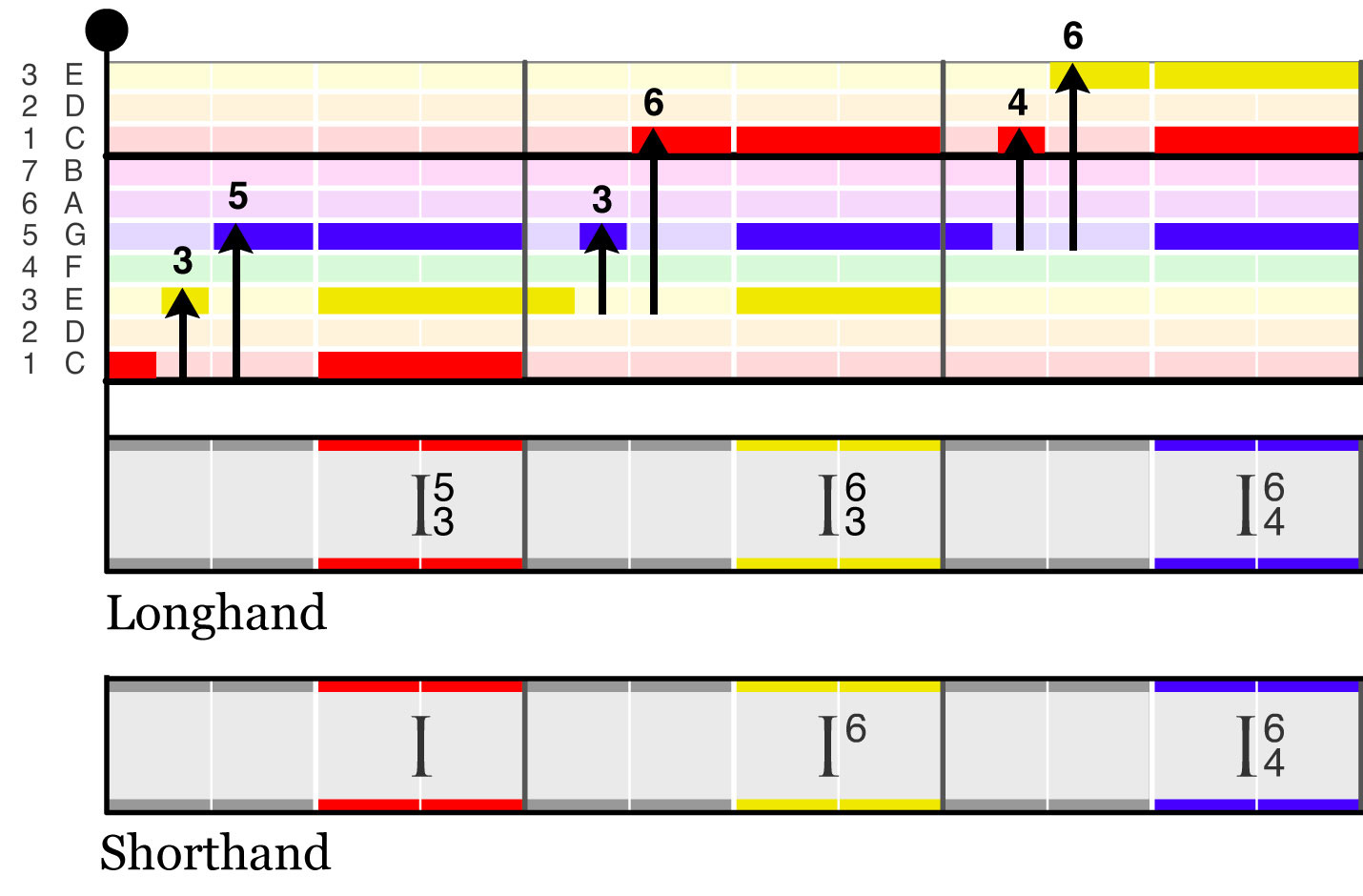

To label whether a chord is in an inversion or not, we follow the convention used by classical musicians. When a chord is in first inversion, a superscript ⁶ is placed next to the chord (i.e. I⁶). Second inversion chords are labeled with the numbers “⁶₄” next to them (i.e. I⁶₄). The (optional) discussion at the end of this section describes where these naming conventions come from.

The next example shows scale degrees 1, 3, and 5 of a I chord arranged with a different note on the bottom to create each inversion of I (the superscripts and subscripts on the chords will be explained shortly).

You may have noticed that inverting the chord also changed the color of the chord block. This is a visual indicator that the bass note has changed, for instance to scale degree 3 (first inversion) and scale degree 5 (second inversion) for the I chord.

We have also shown the inversions of a C major chord in the above example below the Roman numerals to give a concrete example of a real chord and its inversions. a C major chord (made up of the notes C, E, and G) is in root position if the lowest note being played is a C. It’s in first inversion if the lowest note being played is an E and is labeled C/E (read “C over E”). It’s in second inversion if the lowest note being played is a G and is labeled C/G (read “C over G”).

The following diagram has been annotated to show the intervals between the notes in each inversion and shows the longhand and shorthand names of each inversion.

To motivate the naming convention for inversions, consider the first inversion I⁶ chord in the figure above. Scale degree 3 is in the bass, and if we count up from that we see that the next note, scale degree 5, is three notes above. Similarly, the other note in the chord is scale degree 1 which is the sixth note above the bass. Thus, the label ⁶₃ is used to indicate the three-step and six-step intervals that occur when a chord is in its first inversion. Likewise, the ⁶₄ next to the I represents the four-step and six-step intervals that occur when a chord is in its second inversion.

The short hand abbreviation is preferred by classically trained musicians, so that is what we will use throughout this book. The take-away is the super script and subscripts represent the interval spacing of the scale degrees that make up the chord. In practice it’s probably easier to just memorize a “⁶” chord is a first inversion chord, and a “⁶₄” chord is a second inversion chord.

Next up: The I⁶ Chord