When composing in the major mode, your melody normally uses notes from the major scale, but the presence of borrowed chords changes matters. When borrowing a chord from another mode, you are briefly bringing in elements from this mode into your song, and your melody needs to adapt.

For example, suppose your song is in C major, and you are borrowing a iv from the parallel minor. In this case, the relevant scales to consider are the C major scale (the home scale) and the C minor scale (the borrowed scale). While the iv is being played, you will likely want to build your melody with notes contained in these scales, but which notes should you choose?

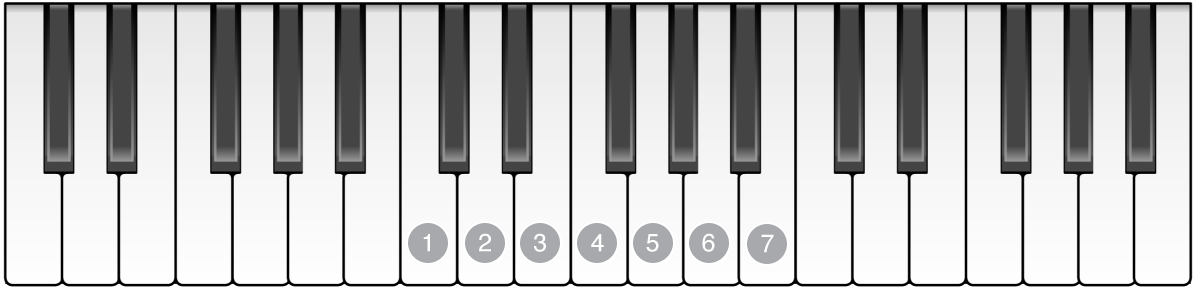

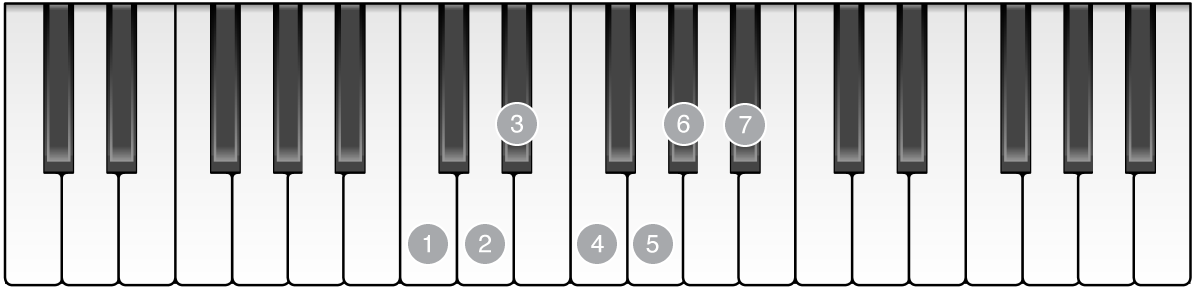

In the previous section we saw that the C major scale and the C minor scale share some notes in common while also having notes that are different:

As shown in the graphics above, these scales have four notes in common and three that are different. Scale degrees 1, 2, 4, and 5 correspond to the same note in each scale, while scale degrees 3, 6, and 7 differ (E, A, and B vs. E♭, A♭, and B♭ in C major and C minor, respectively).

Melodies over borrowed chords using only the scale degrees that are the same in both the original mode and the mode being borrowed from are, in general, a safe bet, because they keep the melody in familiar territory during the surprise of the borrowed chord while simultaneously drawing from the borrowed scale. “Jar of Hearts” by Christina Perri (which you saw in the previous section) is an example of a song that does this. The melody over the borrowed iv from the minor mode avoids scale degrees 3, 6, and 7:

This safe approach is surprisingly common in popular music. By using a borrowed chord, you are already doing something interesting and different, so keeping your melody in safer territory can be a good contrast. Here is David Bowie’s “Starman,” which also avoids scale degrees 3, 6, and 7 over the borrowed "iv":

On the other hand, if you want to expand your melody to include the 3rd, 6th, or 7th scale degrees, you’ll have to decide which scale to draw from — the major scale (3, 6, and 7) or the borrowed minor scale (♭3, ♭6, and ♭7). Using the notes from the borrowed scale, your song sounds further away from home. Likewise, if you stick with scale degrees from the home scale, you keep a more familiar feel.

When these non-shared scale degrees are not in the chord you are borrowing, you can choose whichever option works better for your song. However, if the scale degree is already present in the borrowed chord itself, you should almost always use the borrowed scale degree to match what is in the harmony. In these examples involving a borrowed iv, the chord already has a ♭6 in it (iv contains scale degrees 4, ♭6, and 1), so you should also use ♭6 (instead of regular 6) in the melody to avoid clashing.

“Bohemian Rhapsody” by Queen is an example of a song that uses a borrowed iv while emphasizing the borrowed mode in the melody.

Both the ♭6 (which is part of the iv) and the ♭7 (which is not) are taken from the minor scale and serve to reinforce the borrowed mode.

The following verse from “Take A Bow” by Madonna mixes elements from both the major and minor scales in its melody over its borrowed chords:

In the first phrase, Madonna uses a iv (borrowed from the minor mode) in first inversion to cadence to I⁶₄ (I in second inversion). With its 5 in the bass, the I⁶₄ is less stable and works well to keep the progression from feeling like it has arrived completely back home. The melody over the iv⁶ (iv borrowed from the minor mode, in first inversion) is firmly in the major mode (due to the choice of the 3 from the major scale rather than the ♭3 of the minor scale) and is, in fact, the third repetition of the same one-bar pattern that begins in measure 2. By remaining in the major mode melodically and using repetition, the melody serves to ground the song over the more exotic underlying harmony. In contrast, the melody over the second use of iv in the final cadence breaks with the heavy use of repetition and uses a huge leap to scale degree ♭3 in the higher octave. Add to this the fact that the first seven chords use inversions to create a bass line that descends by step, and you have a very effective and cleverly constructed progression.

Check for Understanding

This exercise will investigate the scenario of composing in the major mode and building a melody over a iv chord borrowed from the minor mode.

Part 1 of 3 When borrowing from a parallel mode, some scale degrees from the borrowed scale are different from their counterparts in the home scale. When composing in the major mode and borrowing from the parallel minor mode, which three scale degrees are different?"

Part 2 of 3 When composing in the major mode, how are these scale degrees notated when they are borrowed from the minor mode?

Part 3 of 3 Would it be a good idea to use scale degree 6 in the melody over a iv?

All the examples in this section have used iv chords borrowed from the minor mode, but the melodic concepts you’ve learned as they relate to this chord also apply to other borrowed chords. In the next section we’ll look at some chords borrowed from other modes. The modal mixtures we’ve looked at so far have all been songs in the major mode that borrow chords from the parallel minor. It’s also common to do the reverse. We’ll start by looking at the most common chords to borrow while in the minor mode.

Next up: Modal Mixture In Minor