So far, you have learned about four of the seven modes: major, minor, dorian, and mixolydian. † The remaining three modes are far less common in their pure form and usually show up as modal mixture; they are the locrian, lydian, and phrygian modes.

What is it about these final modes that makes them less common than the others? Part of the reason may be cultural, but another reason is related to the role that the diminished chord plays in each mode. Remember that because the modes are shifted versions of the same scale, they all consist of the same set of seven basic chords, just ordered differently; there are three major chords, three minor chords, and one diminished chord in every mode. The diminished chord is avoided in most popular music due to its sometimes harsh and unpleasant sound. For example, we’ve seen that in the major mode, the vii° chord is not commonly used. In the mixolydian mode, it’s the iii° chord that is frequently avoided.

One reason the locrian, lydian, and phrygian modes are less common in practice, is that the diminished chord happens to fall on a musically important chord, making it awkward to compose in these modes. In all of the modes we’ve discussed so far, the most important chords have been the “one,” “four,” and “five” chords, the “one” chord being home base, the “five” chord setting up cadences, and the “four” playing the versatile role of pre-cadence chord, cadence chord, and bridge between “one” and other chords in the progression. The importance of “one,” “four,” and “five” is a defining feature of the music we have been learning about. In the locrian, lydian, and phrygian modes, one of these important chords ends up being diminished in quality. Because of this, writing a song in these modes requires careful consideration for how to either work with or work around the diminished chords. Failure to do so can create some undesirable consequences. Let’s see why by considering the locrian mode.

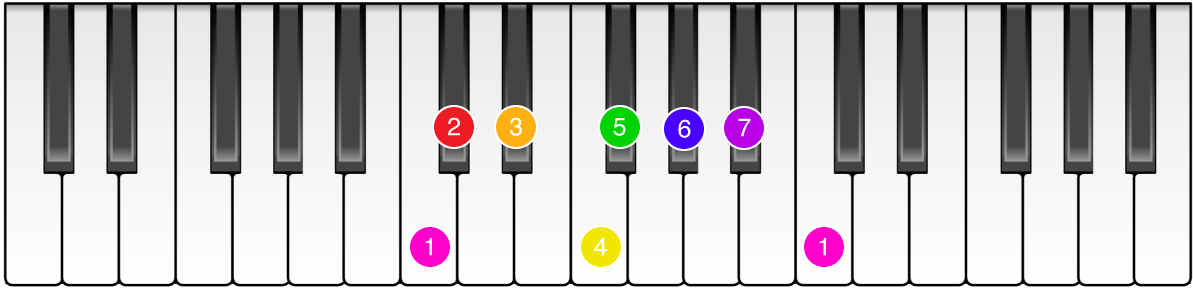

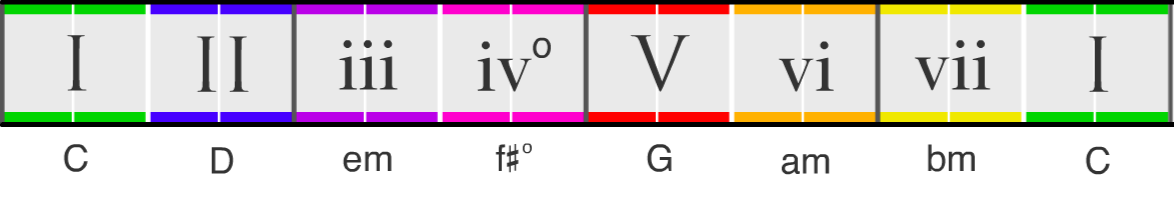

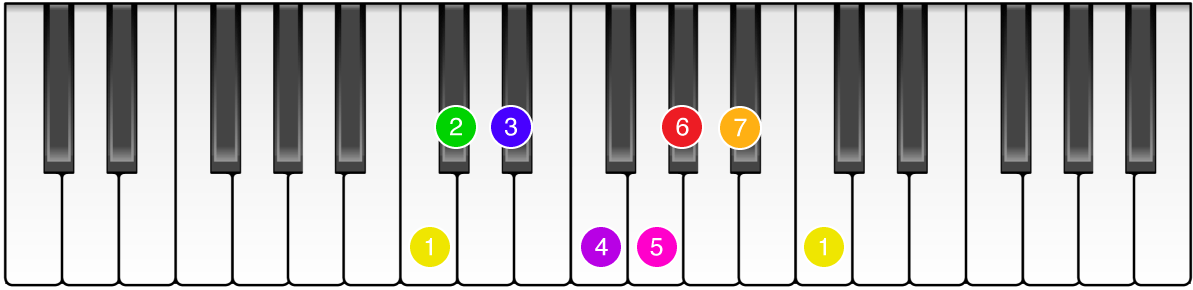

The locrian mode is based on the seventh scale degree of the major scale. Here is the C locrian scale and the seven basic chords that are built from this scale:

Notice that the “one” chord in the locrian mode is a diminished chord. Having a home base with a diminished quality puts the locrian mode at a severe disadvantage. To see why, listen to “Twinkle Twinkle” in the locrian mode:

This diminished home base makes the locrian mode very difficult to work with. You can’t just avoid the home base chord! For this reason, there are not many popular songs written in the locrian mode. In fact, the locrian mode is sometimes called a “theoretical mode” because of its lack of practical use. Fortunately, the other two remaining modes are more practical.\n\nh3The Lydian Mode\n\npLike the locrian mode, the lydian mode is also handicapped by an important chord with diminished quality. In the locrian mode, it is the “one” chord that is diminished ( i° ). In the lydian mode, as we will see, it is the “four” chord with the diminished quality (iv°).

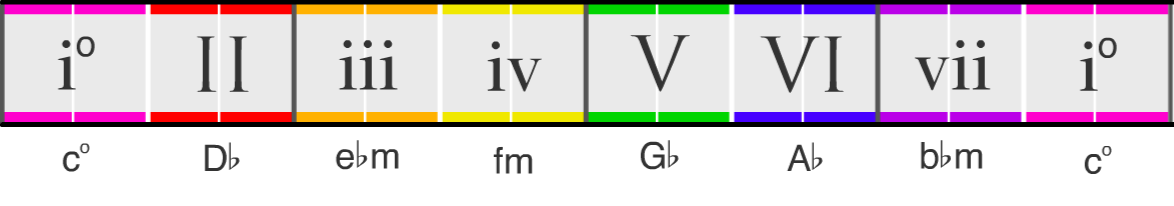

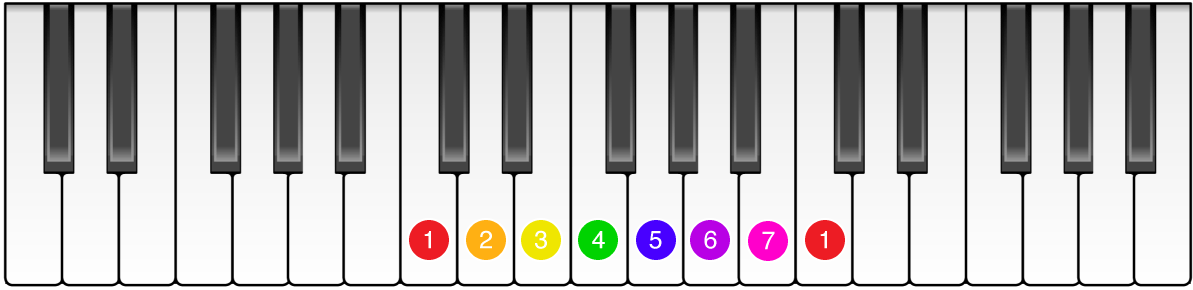

The lydian scale is based on the 4th scale degree of the major scale. Below is the C lydian scale so you can see how it differs from the C major scale:

Like the mixolydian mode, the lydian mode is very similar to the major mode, differing only by a single note; scale degree 4 is sharp relative to scale degree 4 in the major scale. Because of this, songs looking for a lydian feel should focus on melody and chords that incorporate scale degree 4. Here are the chords in the lydian mode:

The chords containing scale degree 4 have a different quality than their respective major mode counterparts: “two” chords are major, “seven” chords are minor, and “four” chords are diminished. As we mentioned earlier, having a diminished iv° makes writing pure lydian progressions more difficult. One notable example is the theme from The Simpsons by Danny Elfman, which fully embraces scale degree 4 and the iv° to create its iconic sound.

“Four” is an important chord, but it’s possible to work around it if you don’t want to use it. In the following excerpt from the “Lost Woods” theme from the video game The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, the progression uses a simple I → V → I → V progression. I and V happen to also be major chords in the major mode, so the progression itself is ambiguous; it could have been written in the major mode. The melody, however, makes heavy use of the lydian mode’s scale degree 4:

A more practical use of the lydian mode is to provide borrowed chords for use in major mode progressions. vii from the lydian mode (a chord with minor quality instead of diminished) is a common choice. vii is often used to arrive at chords with a root on the 3rd scale degree like iii or V/vi. “Yesterday” by The Beatles uses it in this way:

The borrowed major II from the lydian mode can also be a useful chord. II, which contains scale degrees 2, ♯4, and 6, often goes to IV (scale degrees 4, 6, and 1). The smooth transition between the chords works well because scale degree 6 is found in both chords and the ♯4 can slide down to scale degree 4. This use can be seen in “Forget You” by CeeLo Green.

Another song that uses II from the lydian mode in this way is “Dreaming With a Broken Heart” by John Mayer:

II also has a strong tendency to V; however, in Chapter 2, we learned that major II chords are equivalent to the secondary dominant V/V. When going to V, it’s usually more appropriate to think of the chord as a secondary dominant because it shows the function more clearly. For example, in the verse of “Lovely Rita” by The Beatles, one could in principle call the F major chord going to V in the second to last measure a II chord borrowed from the lydian mode. However, labeling it as V/V is a better choice, as it is clearly functioning as a cadence to the V.

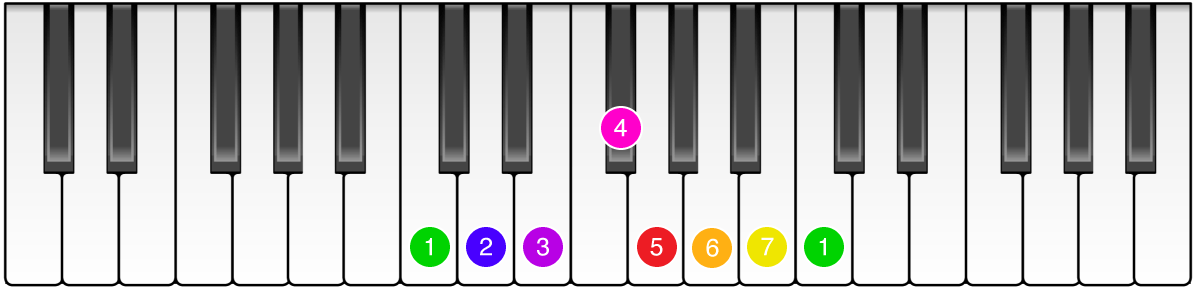

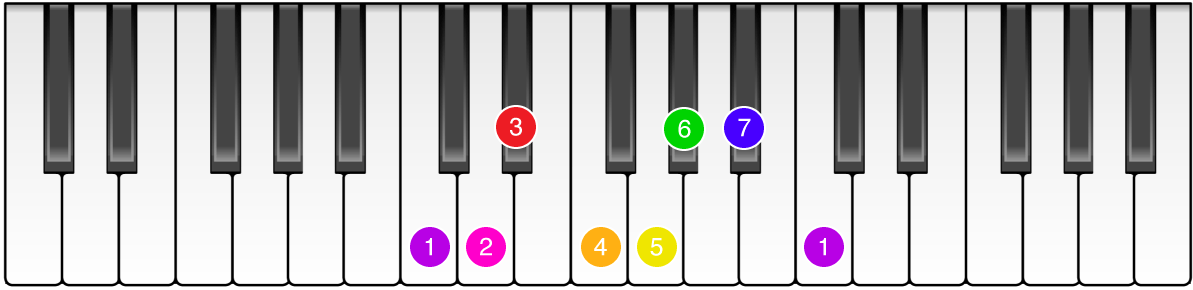

The final remaining mode is the phrygian mode based on the third degree of the major scale. Like the dorian mode, the phrygian mode is very similar to the minor mode. Below is the C phrygian scale so you can see how it differs from the C minor scale:

Notice the only difference with the phrygian scale is that scale degree 2 is one note (a “half-step”) lower. This subtle difference has several important consequences. First, it means that scale degrees 1 and 2 are consecutive notes on the piano, with no note in between. This proximity gives scale degree 2 a natural pull down to scale degree 1, and many melodies in the phrygian mode take advantage of this tendency.\n\npThe second consequence of this difference is that it changes the quality of the ever important “five” chord to diminished (v°). As was alluded to earlier, this greatly “diminishes” its usefulness as a cadence chord and creates difficulties when trying to work around this limitation.

For this reason, many progressions in the phrygian mode tend to just avoid the v° entirely, turning instead to the major II as the primary cadence chord, which has a natural tendency toward i. It’s important to understand that the II chord in the phrygian mode has a different relationship to its home base than the II from the lydian mode discussed above; the latter II, though also a major chord, is separated from its “one” chord by two notes (a “whole step”) and thus does not have the same pull to its home base as it does in the phrygian mode.

In its pure form, the phrygian mode is fairly uncommon. The presence of scale degree 2 is required to distinguish it from the minor mode, but absent a strong cadence from “five,” purely phrygian progressions do not attain the same sense of stability on home base as the other modes. For an example of a song that is purely in the phrygian mode, listen to the following excerpt from Daddy Yankee’s reggaetón hit “Gasolina”:

Another example is “Turn Down For What” by DJ Snake featuring Lil Jon. The chord progression remains static, continuously repeating the i chord, while the melody riffs on the phrygian scale:

It turns out though that the phrygian mode can be made much more interesting with a simple substitution: exchanging the minor home base i for a borrowed major I. The result of this modal mixture is an entirely new sound that is popular in many different parts of the world. Some people refer to it as the “Spanish gypsy mode” due to its prevalence in flamenco music, but it’s also found in Middle Eastern music, Hebrew prayers, and Indian ragas. The following is an exerpt from “Malagueña,” a famous piece written in the flamenco style by Ernesto Lecuona. Notice that the only difference between this progression and the “Gasolina” progression is the borrowed I, but the feel is much different.

The “Spanish gypsy mode” is actually more common than the pure phrygian mode. “Hava Nagila,” a Jewish folk song common at weddings and other celebrations also uses the phrygian mode with a borrowed I from major.

Because of its similarity with the minor scale, its common to borrow chords from the phrygian mode when in the minor mode. The most common chord borrowed from the phrygian mode is the II, which shouldn’t be too surprising given its prominent role distinguishing the phrygian and minor modes. Since scale degree 2 in the phrygian mode is flat compared to scale degree 2 of the minor mode, the borrowed chord is prefixed with a flat: ♭II. This is the same reason that when we borrow VI from the minor mode while in major we use ♭VI (see the section on modal mixture in the major mode for a reminder). ♭II is more common in classical music and was typically borrowed in first inversion (♭II⁶). It tends to act as a pre-cadence chord in the minor mode, as in Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata”:

This ♭II⁶ chord, sometimes called the “neapolitan,” gives progressions a somber air. Although it may not be the best choice for an upbeat chorus, it works perfectly in “Speak Softly, Love” from the film The Godfather.

Check for Understanding

In the lydian mode, what two non-diminished chords are different from their major mode counterparts?

In the phrygian mode, what two non-diminished chords are different from their minor mode counterparts?

Check for Understanding

Explain the difference between the II from the lydian mode and the II from the phrygian mode.

Modes are a great way to alter the sound and feel of a song. It’s the phrygian mode that gives Spanish flamenco music its "flamenco-ness", and the lydian mode that helps give The Simpsons theme its iconic cartoonish twang. But there is more to the feel of a song than the mode it is composed in. Instrumentation, rhythm, and the musical arrangement often play a much larger role than the mode in establishing a particular feel. Yes, the phrygian mode is very characteristic of flamenco music, but so are the rhythms established by the clapping/castanets, the strum patterns on the nylon string guitars, and the singers’ expressions and intonations in the melody.

Modes are limited in their ability to change the feel of a song because, as we’ve learned, they don’t actually introduce any new chords. Every mode uses the same set of chords from the major scale (three major chords, three minor chords, and one diminished chord), just in different contexts and with a different chord as the home base. The reason you hear them differently at all is entirely a result of the rules of functional harmony that your ear has come to expect (and that we’ve been teaching you in this series). Modes are thus a powerful reminder of the importance of knowing the structure and resulting expectations that popular music is built upon.

† The major and minor modes were historically known as the ionian and aeolian modes, respectively.

Next up: Summary