So far, you have learned that:

1. the lettered names of the notes contained in a song are of no help for understanding what is going on unless they are considered in the context of the major scale that a song is using.

2. the particular major scale that a song happens to use doesn’t matter. Most songs can be played entirely with the white keys of the piano (the C major scale), but they wouldn’t sound much different if they were played in some other major scale that makes use of a different set of notes.

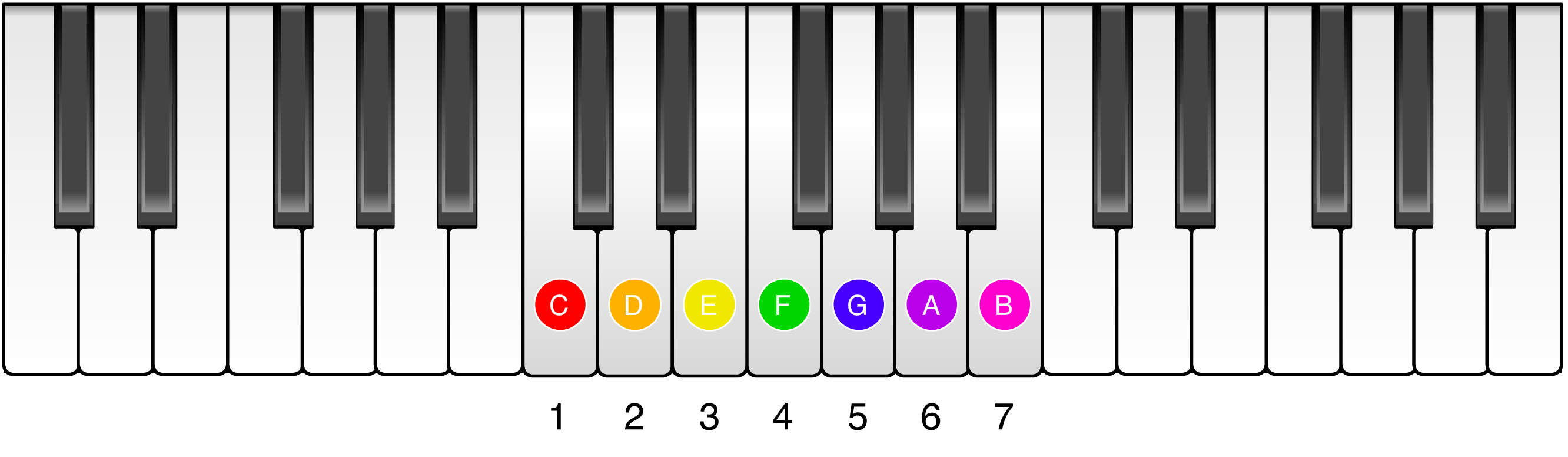

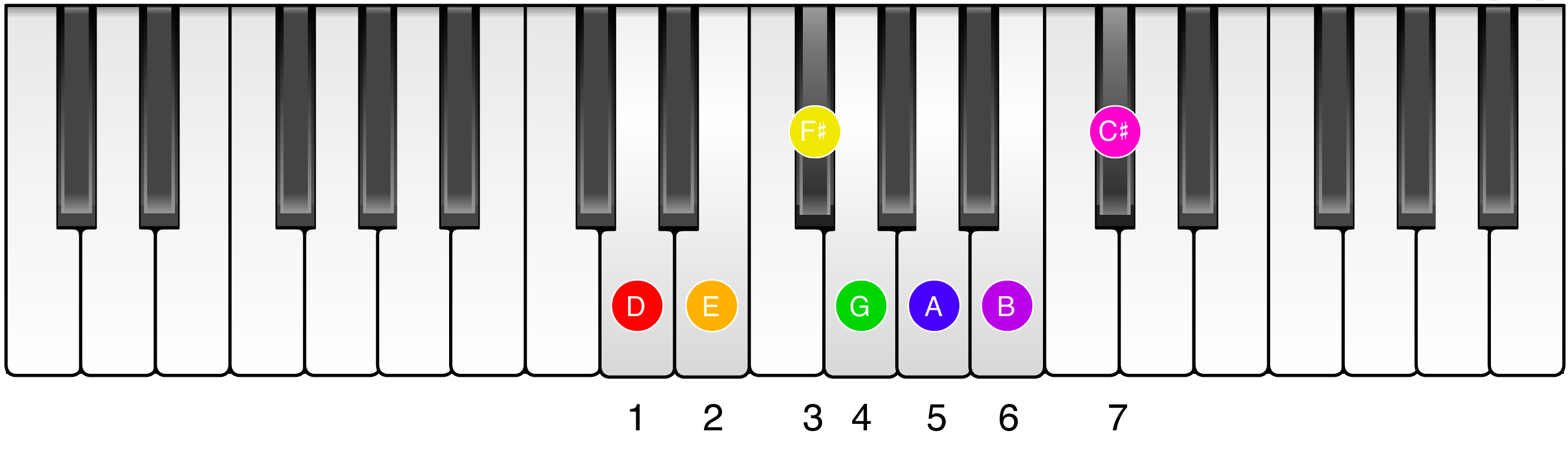

For these reasons, it’s easier and more intuitive to understand music by referring to notes in a song by their position in their scale (1-7) rather than their actual letter names (C, D, E, ..., for example). To introduce you to this notation, often called relative notation, consider the two major scales you saw before but now marked up with numbered labels and colors to emphasize each note’s position in the major scale.

When notes are referred to by their position in a scale, they are referred to as scale degrees. The note D, for example, is scale degree 2 of the C major scale since it is the second note of the C major scale, but it’s scale degree 1 of the D major scale.

One of the most useful things about relative notation is that it enables songs that use scales with different starting notes to be compared side-by-side. For instance, one can compare a sequence of scale degrees rather than two different sets of lettered notes.

Since relative notation makes it easier to learn music, we created a simple way to display music in relative notation. The next example shows the C major scale displayed in relative notation on a staff. Each colored rectangle corresponds to a note. The vertical position indicates its scale degree (1, 2, 3, etc.) instead of its note name (C, D, E, etc). Color is used as an additional visual indicator of each scale degree. Red, for example, is always scale degree 1 regardless of the scale a song is using. Green corresponds to scale degree 4. The length of each note indicates its duration. When you click play, you will hear the scale degrees of the C major scale:

The next example shows the G major scale on the relative staff. Notice that even though the C major scale and the G major scale are different on the piano, they look identical on the relative staff since both use the exact same scale degrees as they play (1-2-3-4-5-6-7-1).

In the previous examples, the fourth scale degree of the C major scale happens to be F. In the G major scale, it happens to be a C. In the relative system, however, both notes are represented by a green scale degree 4 to emphasize their sameness.

A major scale is very simple, and you might be asking how this works with actual songs. Since most songs only use notes from the major scale, they can be represented naturally with relative notation regardless of the key they are written in. Below is the melody from the chorus of “Livin’ On A Prayer” by Bon Jovi visualized with the relative staff.

Thinking about melodies as numbers representing positions in a scale makes it much easier to compare different melodies at a glance. It also makes it easier to analyze and understand melodies because the position of the note in the scale is what determines function rather than the actual note name itself.

The melody from “Livin’ On A Prayer” uses scale degrees 1-1-1-7-6-5-3-4-4-... in succession. If the song happened to use the C major scale, these scale degrees would correspond to the notes C-C-C-B-A-G-E-F-F, but it could just as well have been written in G major where these scale degrees would correspond to entirely different notes (G-G-G-F#-E-D-B-C-C).

When we study the melodies and chords of different songs to look for patterns, we want to compare apples to apples, so the note names just won’t do.

Next up: Chords