Check for Understanding

In the key of G major, what notes are in a I⁷ chord? (The G major scale is labeled on a piano below.)

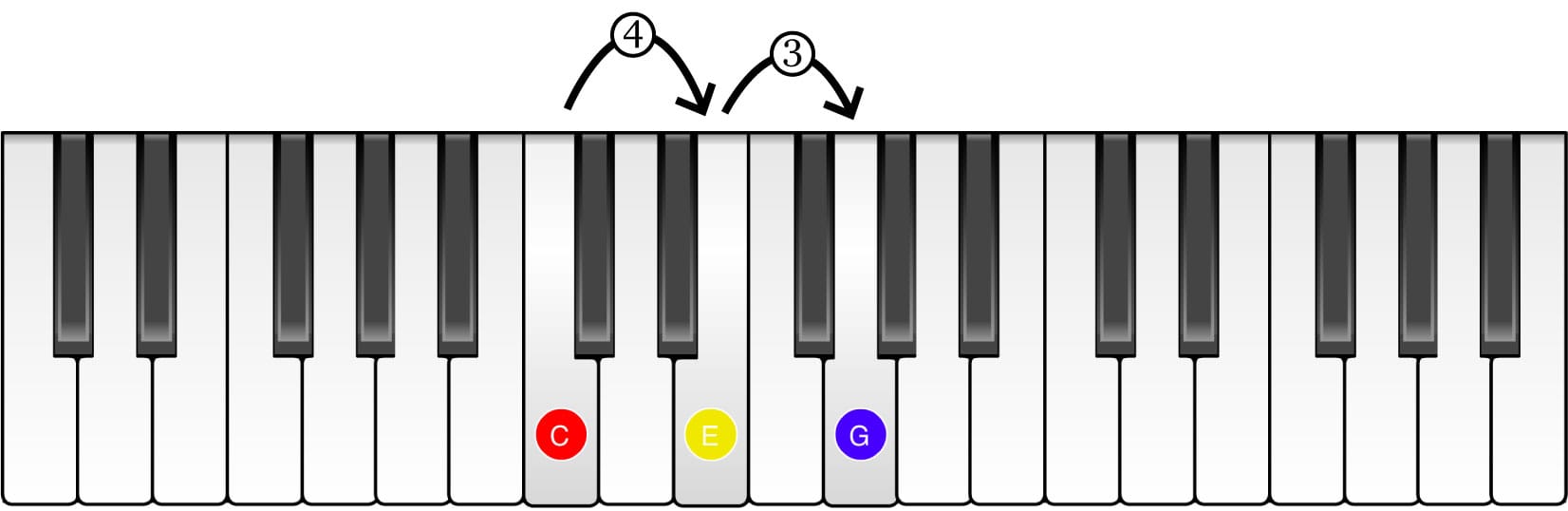

When you were first introduced to the basic chords in Hooktheory I, you learned that each chord has a specific quality associated with it; some chords are major chords, some are minor, etc. The reason for this is that the scale degrees that make up the major scale are not spaced evenly. The white keys of the piano, for example, form the C major scale, and some of these notes have black keys between them and some don’t. We learned that it’s the spacing of the notes in a chord that determines the quality you hear. This explains why, for instance, I chords are inherently major chords, and ii chords are minor chords. Below is a piano showing the I chord in the key of C major (a C chord). The size of the gap between each note in the chord is labeled. Major chords have a gap of four notes between the first and second notes and a gap of three notes between the second and third:

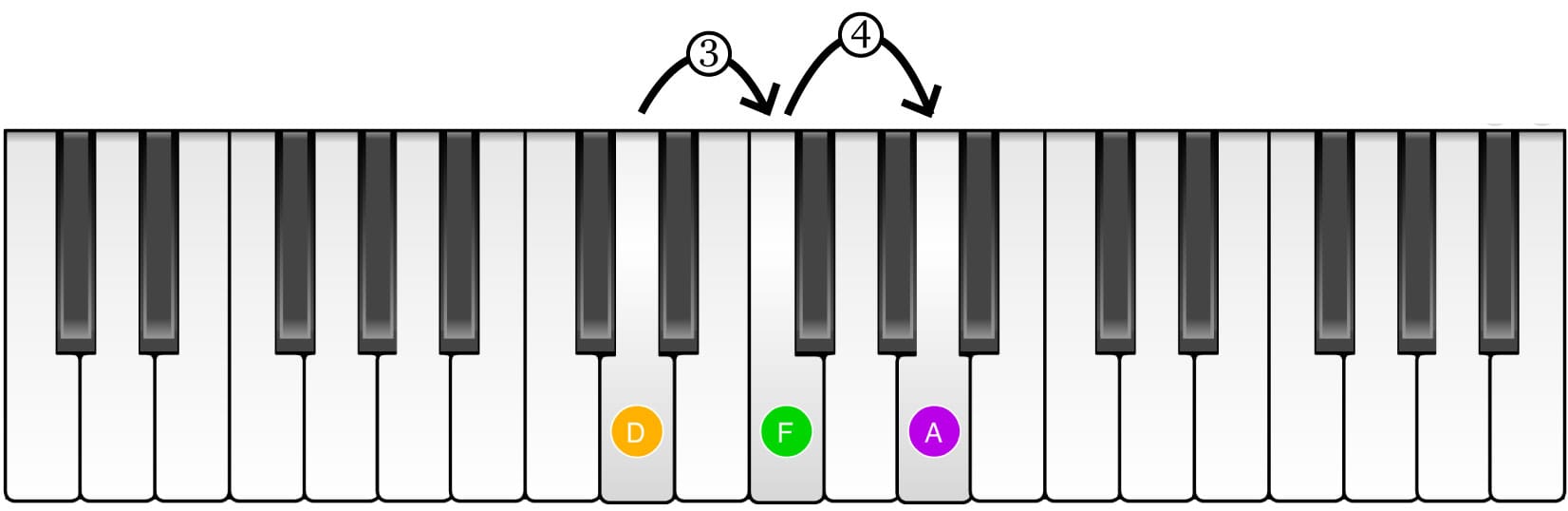

Minor chords, on the other hand, have a gap of three notes between the first and second notes and a gap of four notes between the second and third:

If you need a review of this concept, you can read more about the major scale and the formation of the basic chords in Appendix D: Hooktheory I Chapter 1.

Open Appendix DThe basic chords can be one of three qualities: major, minor, or diminished. However, because seventh chords contain an extra note, their qualities are different than the qualities of the basic chords. Let’s go over them now.

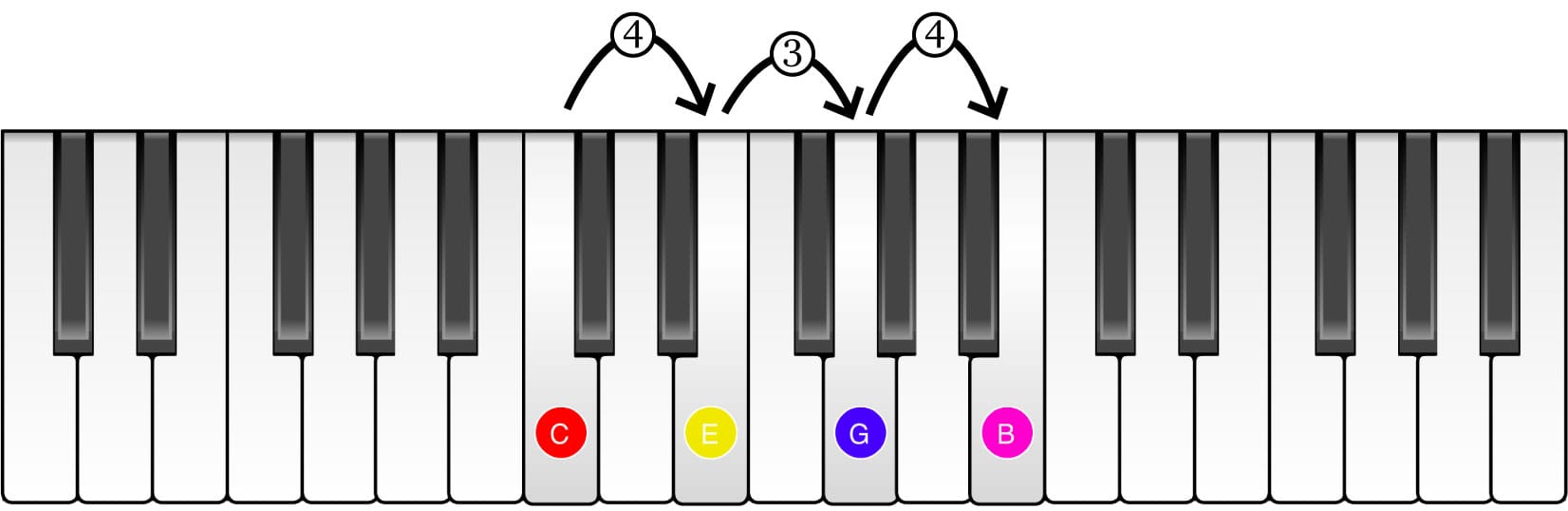

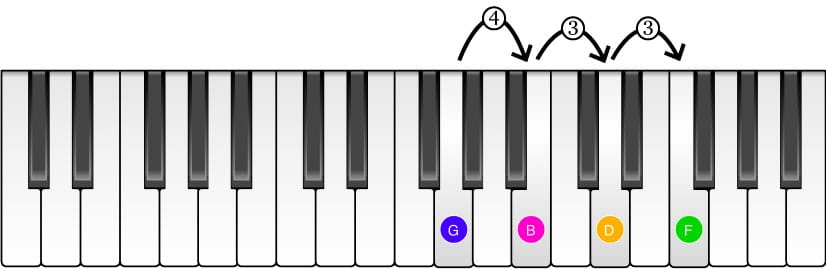

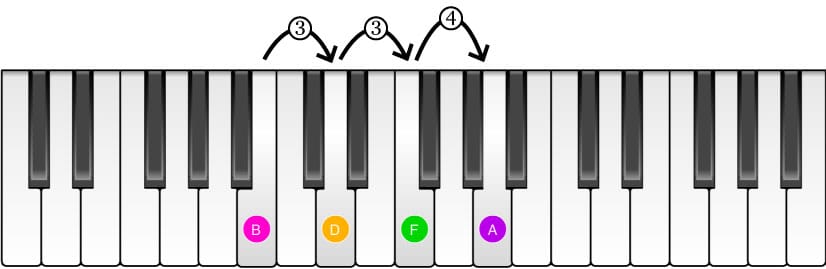

Let’s start with the I⁷ chord. As we learned in the previous section, iI⁷ contains scale degrees 1, 3, 5, and 7. A I⁷ chord in the key of C is shown on the piano below and the gap (or interval) between each of its notes is labeled.

This particular grouping of intervals (four-note gap, three-note gap, four-note gap) creates a chord that has what is known as a major seventh quality; I⁷ chords are major seventh chords. In guitar tabs and sheet music, chords with a major seventh quality are usually labeled with a “maj7,” e.g., Cmaj7. In some contexts, a “△,” a “△7,” or a “M7,” is used instead, e.g., C△, C△7, and CM7 (these are all equivalent).

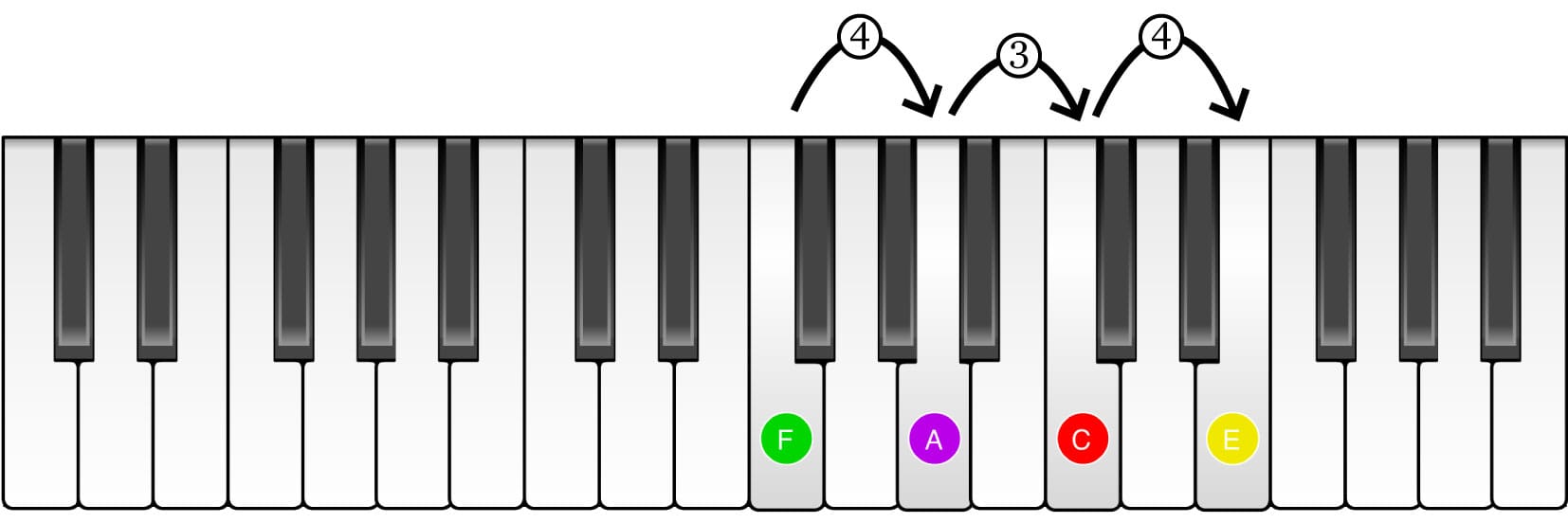

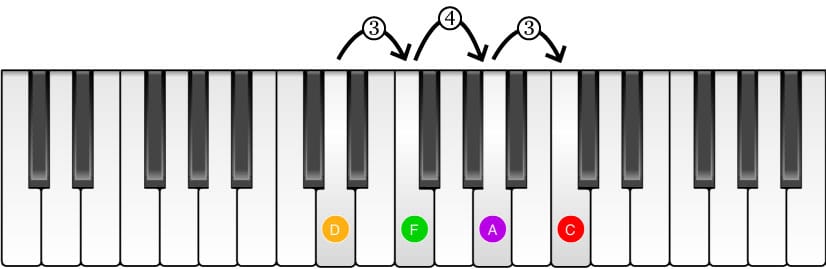

Like I, the basic IV chord is also a major chord, and when it is turned into a seventh chord, the scale degrees are separated by the same gaps found in I⁷. The IV⁷ chord is shown on the piano below in the key of C, with the intervals between the notes labeled.

This means that just like I⁷, IV⁷ is also a major seventh chord.

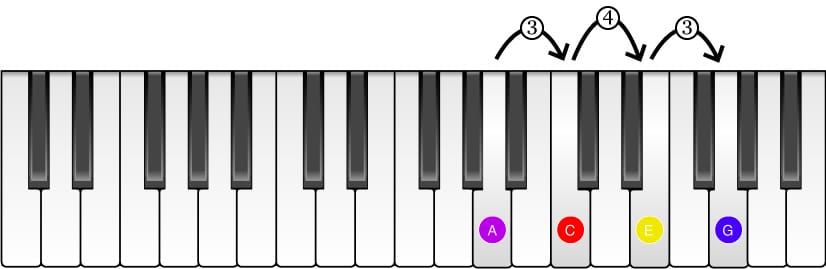

Like I and IV, the V chord is also a major chord, and you might be tempted to think that V⁷ must also have a major seventh quality. However, this is not the case. The V⁷ chord is shown on the piano below in the key of C, with the intervals between the notes labeled.

Unlike I⁷ and IV⁷, the gaps between each of the scale degrees that make up the chord are different (four-note gap, three-note gap, three-note gap). The interval between the final note in the basic chord and the extra note (“the seventh”) is smaller (only three notes away instead of four) compared to the gap found in the I⁷ and IV⁷ chords. This particular grouping of intervals creates a chord that has what is known as a dominant seventh quality; V⁷ chords are dominant seventh chords.

In guitar tabs, chords with a dominant seventh quality are labeled with a “7,” e.g. F7. In the previous example, we saw that in the key of C major, a V⁷ chord has the notes G, B, D, and F. These four notes form a “G dominant seventh” chord (G7). Play the following example to hear a Cmaj7 (major seventh quality) versus a C7 (dominant seventh quality). Can you hear the difference?

Check for Understanding

In the key of G major, what notes are in a I⁷ chord? (The G major scale is labeled on a piano below.)

Check for Understanding

What is the quality of the I⁷ chord?

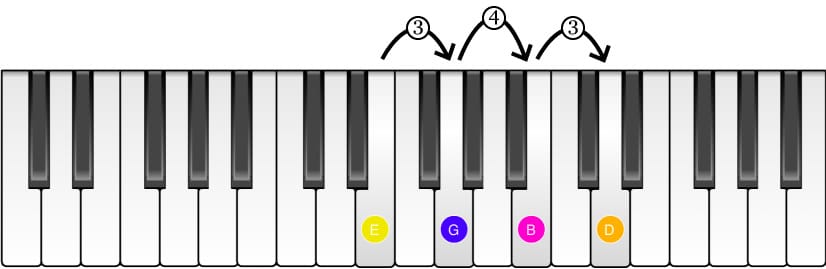

With the three minor chords (ii, iii, and vi), the situation is easier. All of them happen to form what are called minor seventh chords. You might be used to seeing these chords in guitar tabs or sheet music labeled with a “m7” or "min7" (e.g., Dm7 or Dmin7). Below, the scale degrees that form each of these chords are shown on the piano in the key of C. In all three cases the intervals between the notes are the same.

We haven’t spoken much about vii˚ chords yet as they are less common in popular music. We’ll learn more about them and the viiø7 chord, with its bhalf-diminished seventh quality, soon. Until then, here is how viiø7 looks on the piano:

Major seventh, minor seventh, and dominant seventh chords have distinct sounds relative to each other. In the following example, you can hear how a D chord sounds with different qualities. You’ll first hear a D major, followed by a D major seventh, then a D dominant seventh. Then you’ll hear a D minor chord, followed by a D minor seventh.

Below is a table summarizing the qualities of basic chords and their seventh counterparts.

| Chord | Quality | Seventh Chord | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Major | I⁷ | Major seventh |

| ii | Minor | ii⁷ | Minor seventh |

| iii | Minor | iii⁷ | Minor seventh |

| IV | Major | IV⁷ | Major seventh |

| V | Major | V⁷ | Dominant seventh |

| vi | Minor | vi⁷ | Minor seventh |

| vii° | Diminished | viiø7 | Half-diminished seventh |

Check for Understanding

True or false: Adding the seventh to a chord with a major quality always produces a chord with a major seventh quality.

Check for Understanding

Scale degrees 3, 5, and 7 form a chord with minor quality (the iiii chord). What is the quality of the chord formed by adding scale degree 1 to the previous scale degrees (1, 3, 5, 7)?

The extra note in seventh chords changes their sound by adding dissonance. In the next section, we’ll look at how this change in sound alters the function of these chords in popular music.

Next up: Dominant seventh chords